Came Savers: “This was a scam, where is all my money?”

The recent announcement of the liquidation of Came , one of Mexico's largest Popular Financial Companies (Sofipo), has left more than a million savers in a state of uncertainty. For many clients, the measure represents not only the partial loss of their assets, but also the confirmation of what they had been denouncing for months: " This was fraud ."

The voices of those affected are resounding. Some claim this is a similar case to Ficrea , which occurred almost a decade ago, and point to the authorities for their indifference and lack of clear responses.

The Came case began to raise alarm bells in early 2024, when the financial institution stopped providing information to the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV) . Despite having more than 1.6 billion pesos in public funds , the institution began closing branches and denying access to its clients' savings.

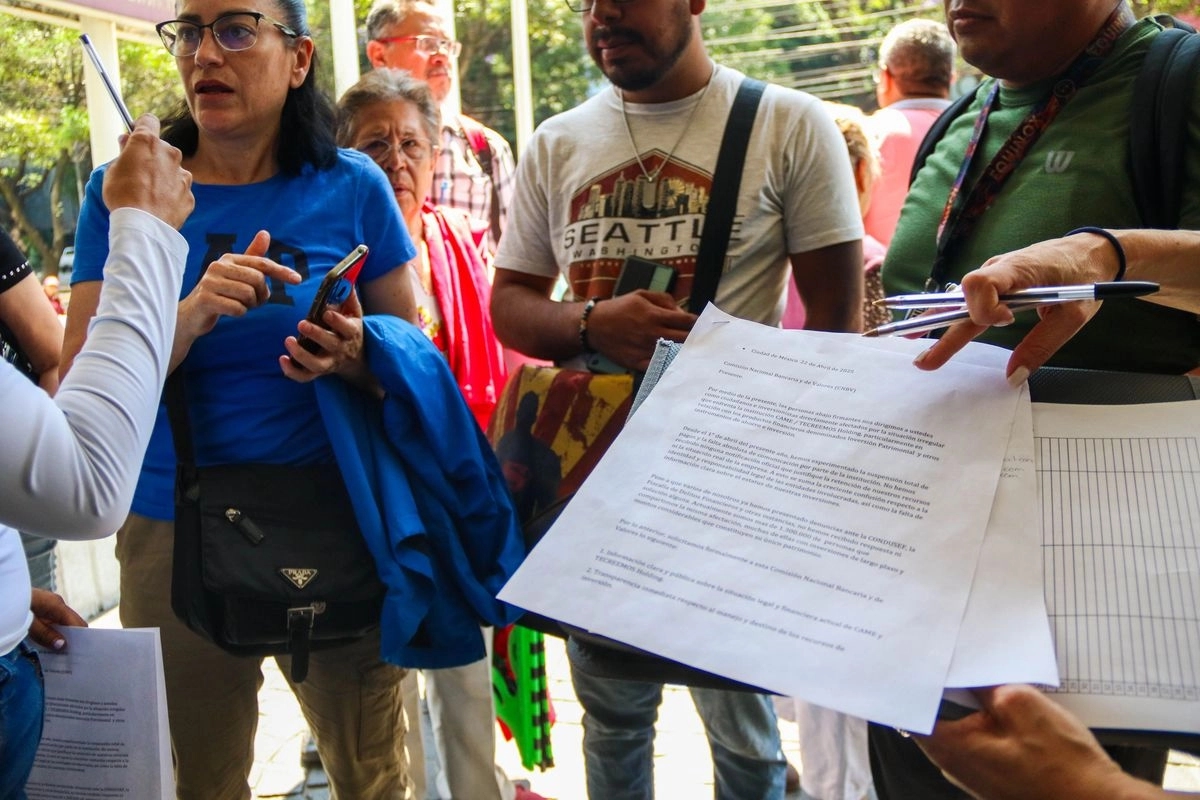

Since January, thousands of people reported being unable to withdraw their money. Discontent grew until, in March, the situation became unsustainable, and a group of affected people began protesting in front of the offices of the CNBV and other agencies, including the Ministry of the Interior .

April 24th marked a turning point. That day, dozens of savers demonstrated for the first time in an organized manner, demanding answers. During a roundtable discussion, CNBV officials acknowledged that they had detected irregularities since March 10th.

The most serious aspect, according to those affected, was that Came continued to accept deposits and grant loans even after it was under surveillance. For savers, this omission is the clearest evidence that the authorities acted too late and allowed the financial damage to spread.

After weeks of protests, the CNBV decided to intervene in Came on June 13 , arguing that there were "accounting irregularities that put the interests of savers at risk." However, the intervention did not bring calm. On the contrary, the protests intensified, and those affected even attended the convention of the Mexican Association of Sofipos in Morelos , where they received only words of "listening" as a form of support.

Social and legal pressure exerted by savers ultimately led to the revocation of Came's license and its liquidation. This measure puts the deposit insurance into effect, guaranteeing the return of up to 213,000 pesos per person .

Although the liquidation provides some protection, for thousands of families the measure is insufficient. Spokespeople like Edna Ávila and Lizbeth Morales claim that their savings far exceed the amount covered by insurance. For them, the crisis represents not only economic losses but also profound emotional strain.

"It's been six months of hell , of not sleeping, of selling off what little you have left," Morales declared. Ávila, for his part, insists that "this isn't bankruptcy, it's fraud" and that another Sofipo can't be allowed to repeat Ficrea's path.

The discontent is also fueled by the perception of indifference from the authorities . Savers complain that the CNBV acted late, allowing Came to continue raising funds until weeks before its intervention.

Now that Came is officially in liquidation, clients can begin the process to recover up to the insured limit. However, the challenge for those who owed larger amounts will be enormous. Many have announced they will continue to pursue legal action against the CNBV and demand an investigation into the whereabouts of the missing funds.

Furthermore, the departure of Jesús de la Fuente Rodríguez from the CNBV, replaced in September by Ángel Cabrera , raises questions about the continuity and transparency of the process. Savers want not only to recover what they are owed, but also to punish those responsible for what they consider a large-scale financial fraud .

The Came case is another blow to Mexicans' confidence in Sofipos (Financial Institutions for Deposits), institutions created to bring financial services to the population. Although deposit insurance provides some security, the recurrence of cases like Ficrea and now Came raises questions about the effectiveness of regulatory oversight.

For many, the message is clear: the risk remains high when it comes to investing savings in small institutions, even those with official authorization. The challenge for authorities will be to rebuild lost trust and ensure that another case of this magnitude doesn't happen again.

The liquidation of Came marks a painful episode for thousands of savers in Mexico. While some will be able to recover some of their money thanks to deposit insurance, many others face irreparable losses. The underlying concern remains the same: where is all the money?

Beyond the legal and financial process, this case reflects the urgent need to strengthen oversight, ensure greater transparency, and effectively protect the citizens who place their trust—and their assets—in these institutions.

La Verdad Yucatán